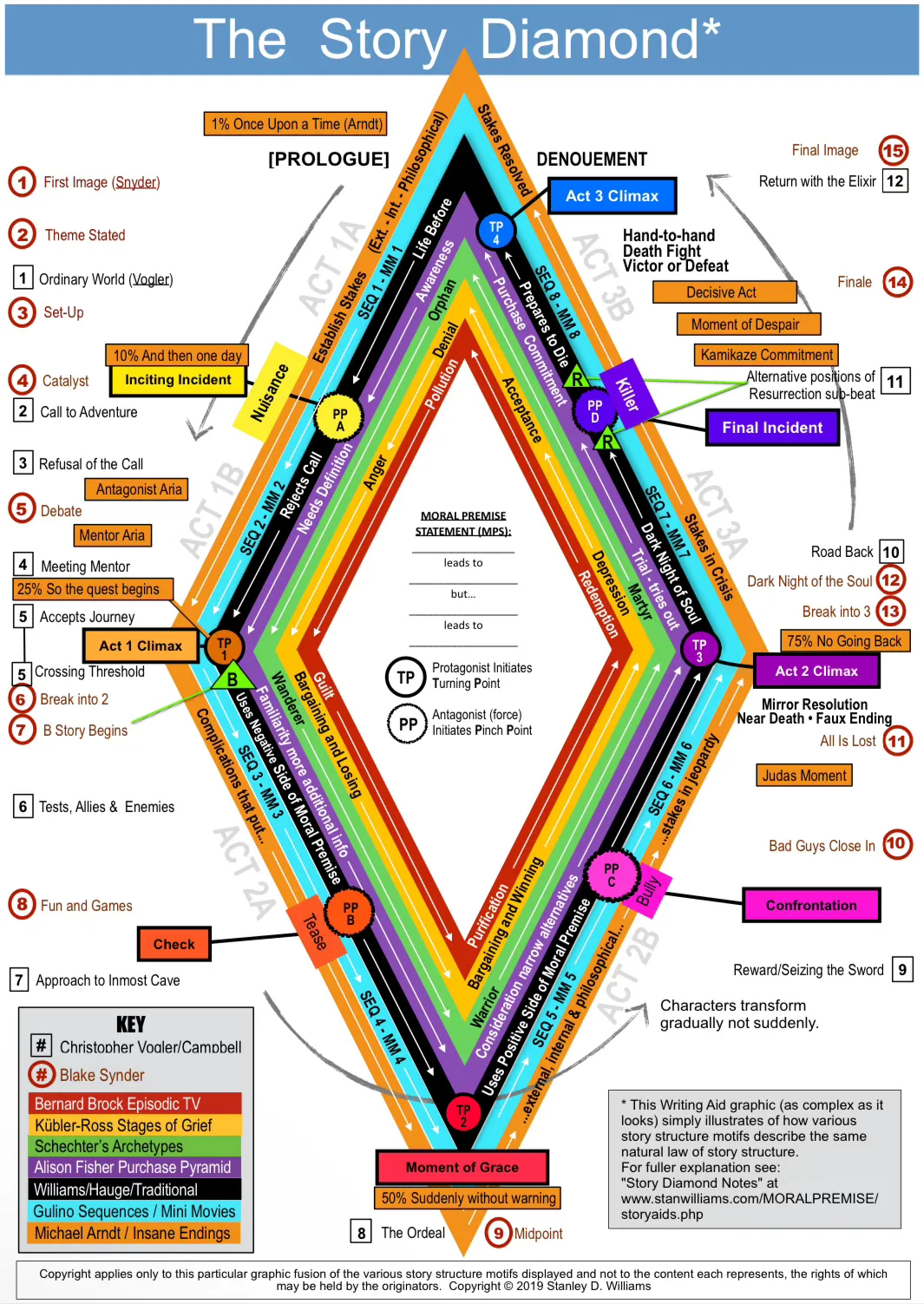

The Story Diamond

I don’t know anything about Dr. Stanley Williams, the inventor of this absolute maze of death, but I’d like to think that he did this for noble reasons. It’s just a horrible migraine to attempt to make sense of.

The Story Diamond and The Moral Premise The Moral Premise describes the core themes or conflict of values that your story is about, and relates those values to the physical actions and consequences we see on the screen, or what a novelist “shows.” That is, at every beat in a story (around the circumference of the Diamond), your characters embrace values that lead them to decisions, that lead them to actions, which result in natural law (organic) consequences. And those consequences motivate your character to make another decision, take another action, experience yet more consequences, and so on. (see diagram at right)

In a story that connects with audiences, characters make decisions that are aligned with either the vice or virtue of the moral premise statement. The consequences of their decisions, over which they have no control, allows the character to interpret the wisdom of their actions in those same moral premise terms. Thus, the moral premise keeps every beat of the story diamond aligned with the one thing your story is about at a physical, psychological, moral, and philosophical level.

The Story Diamond and an Emotional Roller Coaster: The beats most importantly, however, provide target milestones for the writer…around which an emotional roller coaster effect can be created. Without the ups and downs of the story roller coaster your story has no possibility of connecting with audiences…although that statement is an over simplification of all that is needed.

The up and down roller coaster can be measured at a sequence level, scene level, and within a scene as actions are described or lines delivered. The coaster effect comes from an audience’s rational, value and emotional response to what’s happening in the story. On a rational level the audience subconsciously analyzes the protagonist’s journey and evaluates (moment to moment) if the character’s progress toward the goal is being advanced or retarded. On a value level the evaluation may be whether or not the moral premise (value conflict) is true or false. And on an emotional level the coaster ride might evaluate if we feel hope or fear (or happy or sad) for the character, perhaps based on the action taking place on the screen. All of those are interlinked, and the more levels on which the audience is engaged, the greater the audience connection. Michael Arndt in his excellent video Insanely Great Endings, talks eloquently about this as he explains the juxtaposition of the story’s External, Internal, and Philosophical Stakes. (See several posts about the Roller Coaster at the Moral Premise Blog.)

Story Diamond Mechanics:

-

The story starts at the top-left, and rotates counter-clockwise to the top-right. The mid-point (what I call the Moment of Grace—MOG) is at the pointy bottom. It is at the MOG that the character changes motivations in going after the elusive goal. But the “change” is never as quick as the sharpness of the diamond’s vertex indicates. Humans change slowly. Thus, I’ve added a broad “smile” at the bottom to remind you that no change is very fast for the human species, especially when it involves moral values.

-

Each side facet of the diamond represents an equal duration of the story—labeled Act 1 (A&B), Act 2A, Act 2B, and Act 3 (A&B), i.e. 25%. Each of those sides can also be divided in two, as I have indicated by the rough outlined circles, labeled PP for Pinch Points. This divisions of each facet produces eight (8) segments. Some call these “sequences” of 12.5%. Paul Joseph Gulino explains these in Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach.

-

A full explanation of the beats, PP, and TP can be found in the Moral Premise book with an updated explanation at the moral premise blog post: http://moralpremise.blogspot.com/2010/06/story structure-basics.html

-

There are eight colored circles (4 rough edges and 4 smooth) that are regularly spaced around the diamond’s perimeter. These represent an appearance by the antagonistic force which reminds the protagonist of a contrary value that creates the story’s drama (Pinch Points A, B, C, and D - from novel theory as interpreted by Larry Brook), and four Turning Points (TP 1-4) at which the protagonist makes a decision that changes the story’s direction (mostly from Michael Hauge). The like colored rectangles give common names to each of these beats in the story.

-

Major story beats, as depicted in the Story Diamond have two different characteristics. The colored circles and the two “B” and “R” pyramids, represent “moments” (possibly a whole scene) where significant beats occur. These are “momentary” beats. The duration between these “moments” are “sequence” beats and may take a dozen pages to communicate. This gives the story a syncopated rhythm, long-short, long-short, etcs.

-

There are also “moments” that help articulate what the story is really about and the external, internal and philosophical stakes, as Michael Arndt labels them. In Act One there is the Antagonist Aria, where a character representing the antagonist value (Arndt calls it the Dominant World Value, and which the Moral Premise normally refers to as the Vice or Weakness) gives a speech that explains to the protagonist how reality works in the world and that he or she (the protagonist) should not pursue the goal. But then there is the Mentor’s Aria, where a character representing the Underdog World Value or Virtue explains to the protagonist not only how to reach the goal, but why he/she do so. Later in Act 2 Arndt places a Judas Moment, where an ally to the protagonist bails on him and crosses over to the vice or dominate world value throwing the protagonist a defeat. And finally, in Act 3 Arndt places a Kamikaze Commitment moment, followed by a Moment of Despair, and the Decisive Act. I will let Arndt explain all those in his video formerly cited.

-

Names given to the sequence beats by different structure motifs or methods are denoted by the concentric color diamonds. Starting from the inside-out they are, RED: Bernard Brock’s TV Episodic Stages; GOLDEN ROD: Kübler-Ross 5 Stages of Grief; GREEN: Jeffrey Schechter’s four archetypes (via Carol Pearson); PURPLE: Alison Fisher’s 5 Act Purchase Funnel for Romantic Comedy; BLACK: Stan Williams’ interpretation of Michael Hauge’s beats that include the circled PP and TP; and in BLUE “SEQUENCES or MINI-MOVIES 1-8” from Paul Gulino, and in ORANGE Michael Arndt’s Stakes motif explained in his Insanely Great Endings video.

-

Around the document’s perimeter, the boxed 1-12 numbers refer to the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey (location approximate) from Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

-

The (circled) numbers 1-15, intermixed with Vogler’s stages, are the 15 beats from Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat. I think that if Blake was alive we’d have a pow-wow and agree that his beats 12 and 13 should be swapped, as I have done on the Diamond.

-

The number of beats and which ones are used in a character’s arc, are dependent on the needs of the story, genre, character, plot and subplot. That is, a minor character might have only 3 or 5 beats (not the 13-33 illustrated on the diamond). You should expand or reduce as needed. But the Protagonist of a major motion picture or novel will have all of the 13, and possibly the 20 (or more) noted.

-

“Beats” are the logical, dramatic, chunks of evidence that argue for and against the conclusion of the story as defined by the moral premise statement. Think of them as the logical steps necessary to get to the next milestone or turning point. Use only those beats that are necessary. Delete superfluous beats that do not drive the story toward its conclusion.

Miscellaneous: 12. The Diamond illustrates the overall story’s “MAJOR” beats. Every scene is a MINOR beat. Within a scene, every action and line of dialogue is a MICRO beat.

-

For explanations of how each beat and turning point must be irrevocably tied to a true moral premise for the story to resonate with general audiences see The Moral Premise: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success. (http://www.moralpremise.com & http://www.moralpremise.blogspot.com

).

). -

Your story must be about a conflict of fundamental values (a motivating vice vs. a motivating virtue) that are true to the human condition and the moral dilemmas your characters face. Values are those things that psychologically motivate all persons (and thus your main characters) to take some action visible on the screen. All on screen activity originates from a character’s value, morphs to a decision, and becomes visible as an action. Those three things are the character’s doing. The consequence of the action, however, is determined by Natural Law.

-

The two values your story is about must be motivational opposites; e.g. greed vs. generosity, or despair vs. hope. For example: a character must be motivated by some degree of “greed” and/or some degree of “generosity.”

-

Every beat must test the truth of the moral premise, taking the audience on an emotional roller coaster ride as the various characters, in attempts to either achieve or block the physical goals of the characters, test the truth of the moral premise and physically experience the natural consequences.

-

The (1) Value, (2) Decision, (3) Action, (4) Consequence process will alternatively generate the character’s advance or retardation toward the goal, faith in or skepticism toward the truth of the moral premise, and hope or fear in the audience’s emotions…creating the roller coaster you need.

-

During Act 1 and Act 2A the protagonist’s effort at achieving the physical goal is mostly hampered or delayed because he or she is embracing the negative side of the moral premise. At the Moment of Grace (in a redemptive story) the protagonist begins to learn to embrace the positive side of the moral premise. Then during Act 2B and 3 significant progress is made toward the physical goal. In a tragedy the protagonist rejects the truth of the moral premise.

-

During Act 1 the protagonist (and all main characters) are made aware of their psychological vice and their need to go on a journey (in Act 2) to overcome their psychological need so they can achieve their physical goal in Act 3. The physical goal can never be achieved until the character acknowledges and makes progress toward embracing their psychological need. (In Michael Hauge’s terminology the negative side of the moral premise is the character’s “identity” and the positive side of the moral premise is the character’s “essence.”)

Note: I have eleven more pictures of the broken down story diamond, drop me a comment down below if you’d like for me to add them to this post or provide you with a zip file.